Keeping your swimmers on

Investing can be a strange old business that makes otherwise intelligent people behave in – let’s just say – less than logical ways. There is certainly an almost overwhelming inherent competitive urge to ‘beat the market’ influenced and exacerbated by the marketing departments of active fund management firms. Mix that in with rapidly rising markets and a dollop of hubris and that competitiveness can even turn to contempt for those who are not in Bitcoin, tech stocks, Tesla, or some fund that has delivered stellar performance. It can certainly feel a bit like that at the moment. Warren Buffett, in his inimitable way, sums up hubristic investors as follows:

‘Only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.’

Those who are not in these sectors or stocks can suffer a severe sense of missing out – FOMO – which risks tempting them into more speculative areas of investing. That is natural, but it is important to build an investment process that makes sure your swimmers are firmly done up!

We think that this should start with the evidence. Yet as with all research, it may be open to interpretation. One great example is the work done by Professor Hendrik Bessembinder which revealed that of the US$47 trillion of shareholder wealth created in the US equity market between 1929 and 2019, half was generated by around 25,000 companies and the other half by around a mere 80 companies. Comparable observations were made in global markets . You can look at this two ways: pick the 80 great firms and ignore the other 25,000 using your analytical skills to work out who they are and try to shoot the lights out on performance; or recognise that markets appear to be pretty good at reflecting information into prices, and the risk of missing out on these 80 (i.e. <0.5%) stocks is simply too great to risk. How many investors were smart enough to own Amazon in the early days? Well, anyone who owned a US (or global) equity index fund!

In practice, an active fund manager has the opportunity to pick and own the top few companies in their fund. They may get this right or wrong and there is no doubting that this is a tricky business, for which they get rewarded handsomely. The challenging choices do not stop there, they just move down a level; an investor has to then try to pick the manager who they think has picked the right companies and will continue to pick the right companies in the years ahead, not just in the past. Past performance is no guide to future performance, as the required risk warnings always state.

The alternative is to own all companies in the market index and you will be assured to own the next Apple, Amazon or Tesla.

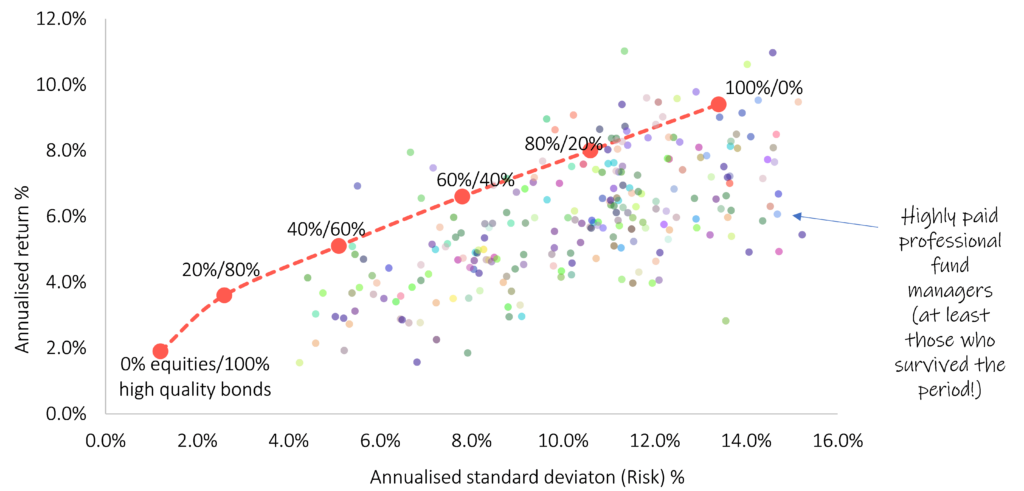

So how do we decide which approach makes most sense? One way would be to look at returns delivered by broad market indices, along the risk spectrum from bonds to pure equities, and compare these to the multi-asset fund families managed by professional active managers, who seek to beat the market. The chart below provides useful insight. The equity index represents developed and emerging markets, and the bond index represents short-dated, high-quality bonds hedged back to Sterling. Costs of 0.5% per year have been deducted.

It is clear that simply capturing the market return has been a pretty effective investment strategy, outpacing the vast majority of professional fund managers and their funds, that have every opportunity to pick winning companies. We also know from a long-running (20-year) study by Standard & Poors that around 90% of professionally managed US, international and emerging markets funds failed to beat appropriate market benchmarks after costs. We also know that there will be some funds that have seemingly stunning past performance, which may be down to skill or luck. As the old saying goes:

‘Markets make managers’

Any manager overweighting US tech stocks will have performed well in the past few years, yet what does the future hold? Will these companies be among the 80 winners of the future, delivering returns higher than the expectations already baked into current prices? The truth is no-one knows.

Our simple message is to avoid the hubris of other investors, stay strong in your conviction in a well-diversified and low-cost approach capturing market returns and only enter the markets with your swimmers firmly on!

Risk warnings

This article is distributed for educational purposes and should not be considered investment advice or an offer of any security for sale. This article contains the opinions of the author but not necessarily Wealth Experts and does not represent a recommendation of any particular security, strategy, or investment product. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable but is not guaranteed.

Past performance is not indicative of future results and no representation is made that the stated results will be replicated.

References

Bessembinder, Hendrik (Hank) and Chen, Te-Feng and Choi, Goeun and Wei, Kuo-Chiang (John), Long-Term Shareholder Returns: Evidence from 64,000 Global Stocks (August 27, 2021). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3710251 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3710251

In the early years, costs might have been higher to implement this strategy, but today OCF costs of good products are around 0.25%.

http://us.spindices.com/resource-center/thought-leadership/spiva/